Aphantasia is the inability to visualize. Otherwise known as image-free thinking.

People with aphantasia don’t create any pictures of familiar objects, people, or places in their mind’s eye.

Do you have aphantasia?

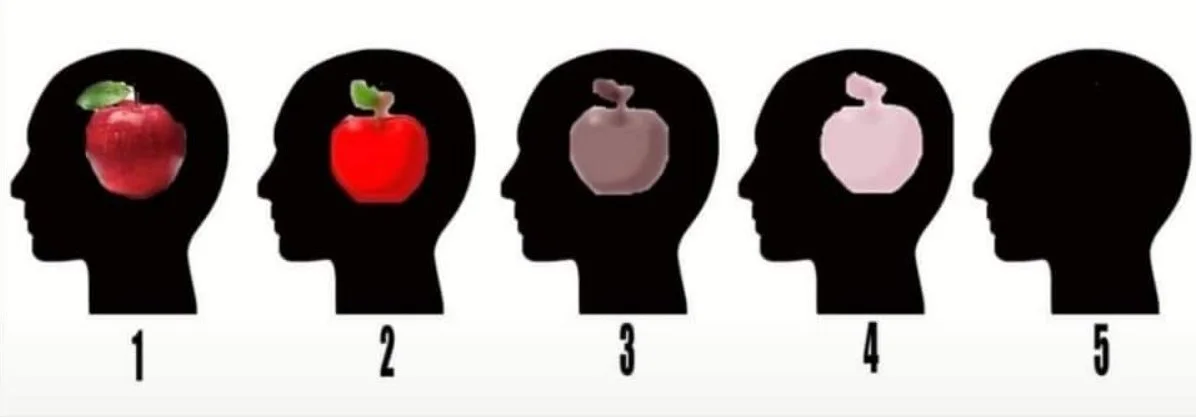

The Imagination Test: Close your eyes and imagine an apple. What do you see?

Social context

People realizing their mind is blind

A research article aimed to clarify the nature of congenital aphasia, whether a person without neurological damage could either not visually imagine an object or not access the images they imagined in their head due to limited introspection and metacognition (Keogh and Pearson, 2018). Past research explored this debate in visual imagery by labelling it either as depictive or propositional throughout the 1970s and 80s. However, recent research metricized this imagery paradigm phenomenon by introducing questionnaires, neuroimaging techniques centered on the visual cortex, and mental rotation tasks. These techniques relied on measuring sensory priming effects, instead of depending on self-reports, by showing a background image when the person was actively imagining objects, which would conflict with their cognitive resources. This study predicted that if a person with congenital aphasia lacked visual imagery, they wouldn’t show priming effects. If congenital aphasia was triggered by limited metacognition, the researchers hypothesized the person would not report mental imagery but would still show a priming effect.

To explore these predictions, the study recruited fifteen consensual people with self-reported aphantasia in the 21-68 age range from an online social media page. They had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, were not screened with a neurological exam, and incentivized with an hourly pay for the 3-hour study and a de-briefing. The control group was based on data from previous experiment results with 209 participants, run under the same stimuli paradigm and experimenter for consistency. Researchers used a binocular rivalry visual imagery task with questionnaires and an assessment to explore a person’s visual imagery ability without the influence of eye dominance as a confound. Each person was placed in a dark room with a monitor that showed two different images, a green-vertical or red-horizontal Gabor patch, to each eye. In the 60-trial experimental timeline, they were cued with an “R” or “G” visual to imagine either patch and shown an imagery period with either a luminance or no luminance condition for 6 seconds. The former showed a consistent black background display during the experiment whereas the latter showed a yellow background, to limit visual attention transients, that increased and decreased during the beginning and end of the 6-second task for 40 trials per block. The participant then rated the vividness of the image they imagined on a 1-4 scale, was shown a binocular rivalry display, and prompted to answer if they saw a green-vertical, perfectly mixed, or red-horizontal Gabor patch labelled as 1-3 respectively. Each person also answered three questionnaires that included, the vividness of visual imagery questionnaire (VVIQ2) on a 1-5 scale, spontaneous use of imagery scale (SUIS), and object and spatial imagery questionnaire (OSIQ) with statements rated from 1 to 5 on agreeableness.

To evaluate the researchers’ hypotheses, the following results explored which imagery paradigm phenomenon was consistent with congenital aphantasia’s symptoms. On the questionnaires, the participants with aphantasia rated poor visual imagery and spontaneous use on the VVIQ, SUIS, and OSIQ’s object factor respectively. However, they showed a significant effect with double the spatial effect, compared to an object component, with an ANOVA under mixed repeated measures. For the binocular rivalry imagery task, aphantasics showed no significant visual priming effect when compared to the control group. During the imagery period, the participants with aphantasia also showed a non-significant priming effect and vividness rating in neither luminance nor no luminance conditions. Thus, they confirmed an aphantasic person’s imagery did not affect binocular rivalry and supported the researchers’ hypothesis of a limited low-level visual imagery ability. Lastly, the findings included a bootstrapping resampling analysis with a 15-person pilot study to account for a representative control group mean visual priming score, recorded 1000 times, in contrast to the small aphantasic sample size. The iterations confirmed the results were not based on a random probability since the control group had a P = 0.001 chance to have the same mean priming score as the aphantasics.

Overall, these findings confirmed the study’s hypothesis that a person with congenital aphantasia showed no priming effects because they simply could not visually imagine a low-level object, not due to a lack of metacognition. Based on previous research, these results support the link of a ventral stream deficit to aphantasics who cannot use their early visual cortex to imagine items but can have spatial imagery and mentally rotate objects. However, the inconsistencies in the study’s methods with variances in stimuli vividness ratings, inconsistent monitor sizes, and non-completed trials due to time constraints could have jeopardized the generalizability of the control group’s data and should be replicated. Though, this study ensured measure validity with low-level visual imagery by using a binocular rivalry illusion that eliminated alternate explanations like an eye dominance bias, kinaesthetic imagery, propositional semantic information, etc. While the participants did not undergo a formal neurological assessment to confirm their aphantasic status, the researchers ran mock-rivalry trials and mental rotation tasks to exclude demand characteristics like a person choosing to suppress their imagination instead of truly not having the capacity to do so. For future directions, the study would benefit from consistent experiment methods that test other cognitive variances with high resolution neuroimaging, like fMRI, in the dorsal and ventral visual processing streams of aphantasics.

References

Keogh, R., & Pearson, J. (2018). The blind mind: No sensory visual imagery in aphantasia. Cortex, 105, 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2017.10.012